If a vote could be taken as to the most popular story in the history of Cortland County, it would undoubtedly point to the General Randall eagle story. This story has been told again and again and with many variations. The following is probably correct in its details because it was told by the son of the person who captured the eeagle ack in 1828, over one hundred years ago.

It was John C. Kinney who caught the bird, not in Dryden, as is generally supposed, but in Kinney’s Gulf, west of Cortland. John was then a boy living on his father’s farm on the Kinney Gulf Road. A sheep from their flock had died that winter, and because it was winter and the ground was frozen, the sheep was thrown out in a field to await warmer weather for burial. An eagle was seen to fly down several times and get a meal from the old sheep.

John’s older brothers set a trap, hoping to catch the bird, but it was too wise to be caught.

John told his brothers that he was quite sure he could get the eagle, and although they laughed at him, he made his plans. Under the snow he planted the trap close by the sheep, and since the ground was frozen too hard for a stake to be driven, John tied two log chains to the trap to make sure that when the bird was caught, it did not fly away with the trap and all. Then he covered everything with snow and waited for Mr. Eagle to arrive.

Sure enough, the eagle came and was caught, just as John had planned. The Kinney boys put together a rough cage and had a gloriously exciting time getting the strong, wild bird into its prison.

John sold the eagle to William Bassett, a jeweler of Cortland, who put it in an iron cage especially made for the purpose. It was a large one, standing six or seven feet high.

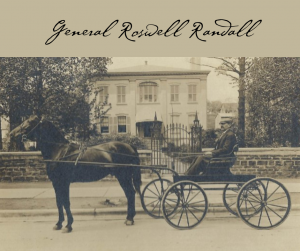

Poor eagle! Life was not so pleasant as when it flew among the hills of Kinney Gulf. Mr. Bassett sold the bird to General Roswell Randall, who placed the cage on his front lawn where the Cortland Standard block now stands. Then it was removed to a little triangle of grass where Watson’s drug store is now located. (Note: this store was in the Squires Block, the old clocktower building.) This was near the door of General Randall’s store, which stood where is now the Parker block (Note: the old clocktower building was also called the Parker block at a later date), and people going and coming always stopped to say a word to the captive eagle.

It was a very large and handsome bird, but it could never be fully tamed.

Fourth of July, 1831, was no common celebration. Flags were flying around the four corners where General Roswell Randall had built his house and hotel and store, and a band was playing patriotic music all day long. There were men still living who had fought in the Revolutionary War, and could remember the joy of that first Fourth of July in 1776 when the Declaration of Independence was read in Philadelphia and the old Liberty Bell had pealed out its jubilant news to all the country.

Early in the morning a cannon roared through the seven valleys of Cortland Village and echoed from South Hill and Salisbury Hill and all the other hills round about. People were streaming into town from Homer and Virgil and Truxton and far Cincinnatus.

They came afoot and on horseback—whole families in lumber wagons with spans of horses. The two churches of the town, the Methodist and Presbyterian, were ringing their bells in wild glee, and no doubt there were active boys pulling the bell ropes. The Academy bell was ringing, too—The Academy between the two churches. Something was going to happen. Old Main Street was crowded with people and horses and wagons. Boys and girls were sitting on the Randall wall.

Whether General Randall was tired of trying to tame a wild eagle, or bore a troubled conscience for keeping in captivity one which stood as an emblem of American liberty, we do not know.

He talked with William Bassett, the brother of Mrs. William Randall. Being a silversmith, Mr. Bassett made a silver clasp and engraved upon it the words “To Henry Clay, Louisville, Ky, from William Bassett of Cortland Villa., Cortland Co., N.Y.” This he placed on the bird’s leg.

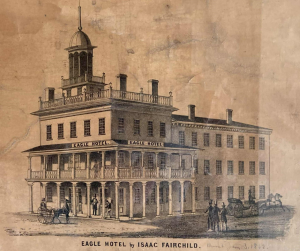

Thus it was that on the Fourth of July, 1831, William Bassett took the eagle to the top of the cupola of the Eagle Hotel, standing where the Messenger House now stands (Note: Cortland Diner stands here today.), and faced the bird toward the southwest. With an immense crowd watching, the eagle was set at liberty. It stood erect upon the cupola, flapped its wings three times, and with the military corps firing guns and the citizens swinging their hats, the eagle vanished from sight.

On July 11, 1831, the sequel of this story transpired. An Indian shot an eagle on a high bluff, bordering the Mississippi River, three miles of Dubuque. It measured three feet and eleven inches from tip to tip of its outstretched wings. On its leg was riveted a silver clasp with an inscription thereon just as William Bassett had engraved it. Eventually the silver clasp came back, and ever since that day people have loved to tell the story of General Randall’s eagle.

The latter part of this story came from the lips of Miss Wilhelmina Randall, who lived all her life of ninety-three years in the beautiful old house on Main Street known as the Randall mansion. She was a little girl eleven years old when the eagle took his flight from the Eagle Hotel, and she told the story with all the pleasure of one who saw it happen.

She added one more detail which is not mentioned by anyone else. She said that when the bird began its flight it was a little bewildered. Three years had passed since it had tried its wings. It circled around a few times and flew over to the orchard which stood behind the Randall mansion, and there it alighted. A crowd of boys rushed toward it and the bird flew away over Court House Hill, headed for the west.