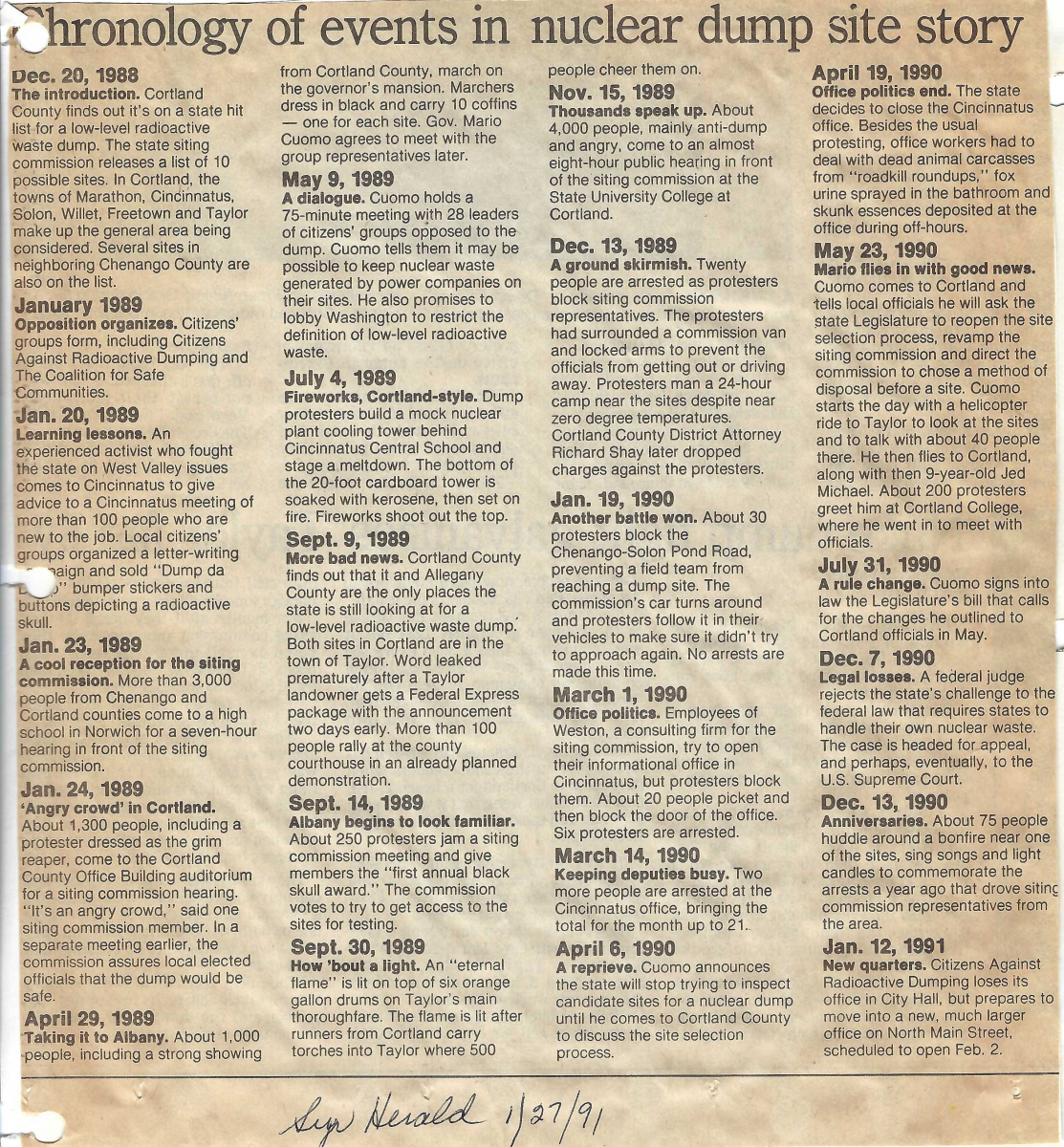

Chronology of events from December 1988-January 1991

The fight continued on, reaching a climax when the Supreme Court struck down the 1985 amendment to the 1980 law, targeting the provision that made states assume ownership of their nuclear waste by January 1, 1996 if they didn't have another means of disposal by that point. In May of 1993, the five proposed sites including the two in Taylor were finally set aside. And in June 1995 the Siting Commission was defunded, marking a final end to the fight.

Introduction

Between 1989-1995, the community of Cortland County rallied together in a way not seen before or since in an effort to save their home and families from the threat of a radioactive waste dump in their back yard.

In 1980, a federal law passed that made states responsible for the disposal of their own low-level radioactive waste, and required a site be up and running by January 1, 1993. On December 20th, 1988, Cortland County residents were shocked to find out that the Low-Level Radioactive Waste (LLRW) Siting Commission tasked with the mission of finding a suitable location for the waste dump listed Marathon, Cincinnatus, Solon, Willet, Freetown, and Taylor as potential sites. Other candidate sites included two in Chenango, one in Orange and Ulster counties, one each in Allegany, Cayuga, Clinton, Montgomery, Oswego, and Washington counties. Over the next two years, the Siting Commission would be working to narrow the candidate sites down to a spot measuring one square mile.

Citizens Unite

Almost immediately, grassroots coalitions were formed as residents of the listed towns joined with their neighbors to fight the state commission. While the Coalition for Safe Communities was sanctioned by town boards to start gathering information to develop a case against the dump, a private citizens’ group- Citizens Against Radioactive Dumping (CARD)- formed as an attempt to sidestep some possible red tape and delays associated with moving through local government chains. Over the course of just over five years, CARD and its members would play a key role in educating and rallying the community, as well as ensuring their voice raised in protest was heard by the Siting Commission, legislators, the governor, and even beyond to nationwide platforms.

More than 3,000 citizens of Chenango and Cortland attended an informational meeting on January 23, 1989 in Norwich, and the next day over 1,300 Cortland residents crammed into the County Office Building with chants of ‘Dump the Dump’ and signs reading ‘Hell No. We Won’t Glow.” Obvious concerns voiced at this time included hazardous hilly roads, and the complaint that rural communities had been unfairly singled out with the hope that residents would not have the power to fight back. CARD representative Patti Michael spoke out against the commission saying, “You are terrorists, you have terrorized our communities, our children and us. Conveniently and strategically, it seems, you left us little time to get organized and learn. But we did.”

And learn they did. CARD and its members would work hard to educate themselves not just on the topics of radioactive waste and its disposal, but also on methods of effective peaceful protest and how to catch the attention of reporters. What they found to be highly successful was the use of outrageous costumes- from the giant “Cuomo head,” to the various “mutants” at the Mutie Pageant held on Love Canal Solidarity Day in Albany at the Capital on 10/1/1990, to a woodchuck costume worn in proud defiance of the intended insult toward Cortland residents simply being a “bunch of woodchucks.”

Throughout 1989, protestors further organized and worked hard to advocate to their community to speak out. Amazingly, individuals from all walks of life joined in the fight, including farmers, lawyers, teachers, stay-at-home moms, bus drivers, and legislators. Groups made multiple trips to Albany to lobby Governor Cuomo, who made what promises he could to assuage their concerns. Fears only deepened when in September it was announced that the only proposed sites that remained on the list for consideration were two in Taylor and three in Allegany County.

Skirmishes, Arrests, and Compromises

Shortly after, Siting Commission representatives started to attempt to visit the proposed sites but found themselves blocked by protestors. These interactions reached a boiling point when twenty protestors, the “Taylor Twenty,” were arrested, with charges later dropped by Cortland County District Attorney Richard Shay. More arrests would occur in March 1990 as picketers blocked access to the informational office established by a consulting firm for the Siting Commission. Besides the usual protesting, the information office workers also had to deal with dead animal carcasses from “roadkill roundups,” fox urine sprayed in the bathroom, and skunk essences deposited during off-hours. These methods proved controversial, even amongst members of CARD. But they were effective in bringing about the closing of the office just over a month after its opening.

In May of that year, Governor Cuomo helicoptered into Cortland County, first visiting the sites in Taylor then making his way into Cortland (giving nine-year-old Jed Michael a ride along the way) to meet with officials. Gov. Cuomo went on to sign a bill that called for a reopening of the site selection process, revamping of the Siting Commission, and direction to choose an alternate method of disposal before a site.

Taken to the Supreme Court

In the meantime, a case challenging the federal law was set before a federal judge who rejected it in December 1990. The case then made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court where Justice Sandra Day O’Connor described the law, with apparent sarcasm, as a “pretty clever scheme.” Finally in June of 1992, the Supreme Court declared that it was unconstitutional to make states, rather than the waste generators, assume ownership or title to the waste upon the event that the state does not have a means of disposal by January 1, 1993.

The fight was not yet over, however. The question of where the waste should go remained unanswered, and Cortland was still on the list of proposed sites. In November, Cortland County legislators passed a law that declared the county a nuclear-free zone. The law was mostly symbolic given that the state could override it, but it was seen as an important step for protecting against the dump. Finally, in May 1993 the five proposed sites including the two in Taylor and three in Allegany County were set aside. A decisive end to the fight came in June of 1995 when the Siting Commission was abolished.

Conclusion

Through perseverance, creativity, community cooperation, and the sheer will to protect their home and families, the citizens of Cortland County fought and won the battle, not accepting the placement of a radioactive waste site in their community. Many of the protestors went on to continue to fight other environmental issues, including advocating for alternatives to nuclear energy. Thirty years later, these events are already fading from memories, but we at CCHS find it necessary to preserve and share this story of Cortland County’s victory!

From September 2022-March 2023 an exhibit at the Cortland County Historical Society will display costumes used in the fight along with more photographs, video footage, and more!

If you would like to learn even more about these events, there are two binders full of newspaper clippings gathered during the events, as well as multiple boxes of photographs, newsletters, meeting minutes, etc. A collection of items donated by Jim and Jean Weiss has been digitized and is available on the New York Heritage website via the link below. Also linked below is an oral history interview with the Weiss’ about their experience in the fight.